Fact vs. Fiction: Defining Fake News and Tackling the Industry-Wide Challenge

As the topic of fake news continues to make headlines, it becomes more important to be able to distinguish what is real news versus what is not. However, that distinction is not always an easy one to make.

While the term “fake news” seemed to arrive just in time for the U.S. presidential election, it isn’t exactly new. The intentional making up of new stories to fool or entertain has always existed. However, the difference is that, today, social media and digital distribution channels have made it more difficult to tell “fake news” apart from “real news.”

Fake News in the Spotlight

The term “fake news” rose to popularity when Facebook faced a backlash for allegedly influencing the 2016 presidential election through the proliferation of made-up stories in users’ newsfeeds and related links. For example, the much-shared claim that the Pope had endorsed Donald Trump.

Although Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg initially rejected the accusations, he then went on to write an open letter to readers about what the company was “doing about misinformation.” Zuckerberg mapped out a plan calling for stronger detection, easy reporting, third-party verification and other steps aimed at disrupting the fake news economy.

Google also came under fire for sharing fake news as part of search results, after it displayed a WordPress site as a top hit with information that Trump won both the popular as well as the electoral college votes.

At the time, Andrea Faville of Google issued a statement: “Moving forward, we will restrict ad serving on pages that misrepresent, misstate or conceal information about the publisher, the publisher’s content or the primary purpose of the web property.”

Meanwhile, in the months since the election, the meaning of fake news has continued to evolve in the cultural lexicon. President Trump has consistently used the term to refer to media brands with which he disagrees. He famously called out BuzzFeed and CNN as fake news sources during a January media event, and excluded them—along with The New York Times and The Los Angeles Times, which were also labeled fake news—from an informal White House press briefing in February.

So the question becomes: What exactly is fake news and how can one recognize and avoid it? Moreover, is “fake news” even a term we should be using, given its denigration in the cultural lexicon?

Sifting Fact from Fiction

The truth is that these are not easy questions to answer.

Media outlets such as PolitiFact and Snopes have dedicated channels to check the accuracy of news reports and employ entire staffs to weed through sources.

Meanwhile, despite their best efforts, even legitimate news sources occasionally make mistakes. The Guardian, for instance, reported in December 2016 that actor Michael Sheen was trading in acting for politics. However, Sheen completely denied the story and declared that he was not “quitting acting and leaving Hollywood” to go into politics.

Does that mean The Guardian publishes fake news? The answer is a resounding “no.” Premium publishers should not be relabeled as “fake news” based on occasional editorial errors. In fact, for years, credible news sources have had a process for printing corrections simply because that is part of the news business. These publishers continue to uphold this standard, correcting errors when they are made as they always have—but in the age of social media, where stories are retweeted and shared in real-time, it can be a challenge to ensure the most accurate story is always broadcasted first.

As for whether we should be using the term “fake news” at all—that’s still up for debate. However, it is notable that some, like Facebook, are opting to reframe the dialogue by referring to this type of content as “misleading news” instead.

Fake News: The Challenge

And yet, while fake news may or may not have swayed the election, it can still have troubling, real-world results. In December 2016, a man fired an assault rifle in a Washington, DC, pizza parlor, in an incident dubbed “Pizzagate.”

The gunman was investigating an unfounded “conspiracy theory” in which the business was a front for a child sex ring run by presidential candidate Hillary Clinton and her campaign manager.

The conspiracy theory initially spread through viral emails, discussion threads, and social media in the weeks leading up to Election Day, reports PolitiFact. From there, fake news sites began spinning out versions of the unproven story.

So, how can reputable media outlets and social networks prevent the spread of fake news? If they ban a website’s feed, does that border on censorship and infringe on First Amendment rights?

When Business Models and Fake News Collide

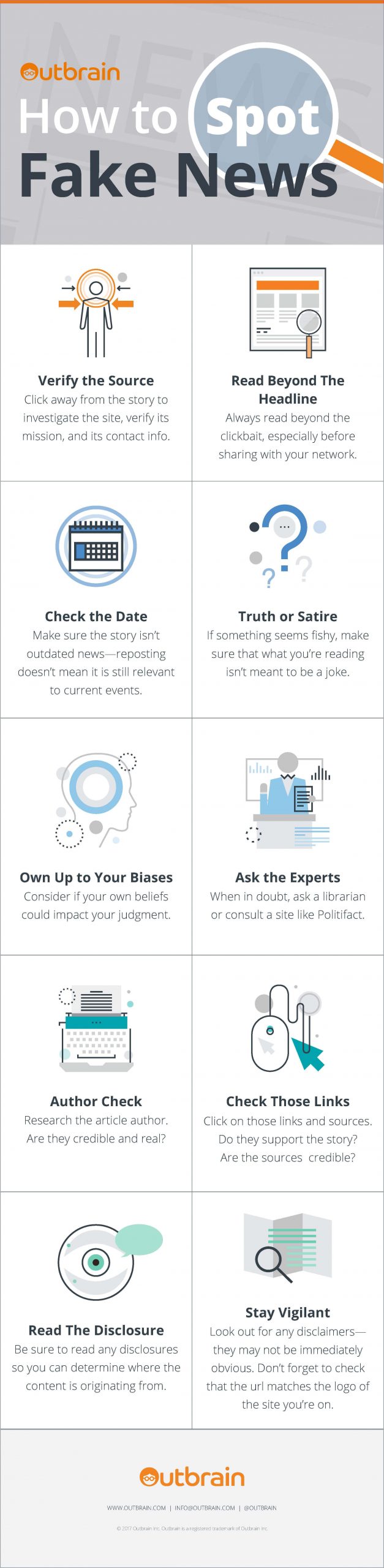

In particular, Facebook and Google have been singled out for their roles in spreading fake news. Social media platforms, like Facebook, have traditionally been hands-off of the content shared on its platform, encouraging virality instead. However, following incidents such as Pizzagate, it has made moves to educate its users and employ new fact-checkers for its content. For example, it points users to a list of “Tips to Spot False News.” Recommendations include: “Be skeptical of headlines,” “Look closely at the URL,” “Investigate the source” and “Watch for unusual formatting.” (See below for an infographic offering our own tips too.) And if a user suspects a Facebook post is fake, they can take steps to report it as “false news” to the network administrators. If third-party fact-checkers confirm these are fake, posts then appear as “disputed.” Additionally, just yesterday, Facebook rolled out a “disputed” warning label to stories that could be perceived as misleading.

Google has also taken steps to weed out fake news. Search results will remain the same but a new “Fact Check” tag serves a small breakout box from a fact-checker site at the top of the results. Only time will tell if Google makes additional strides to address misleading content. For example, tackling brand safety concerns, given that advertisers frequently have no idea where their ads are being served to audiences.

Meanwhile, here at Outbrain, we’ve focused on three key areas and taken clear measures to address the issue.

1. For more than 10 years we have focused on building the most premium native platform in the world—a network that is made-up of 75% of the globe’s premium publisher brands. We do not place our widget programmatically. Instead, we have direct publisher relationships that afford increased brand safety for marketers, and give Outbrain more control around what other advertisements are displayed adjacent to our brand partners than through other mediums (e.g. display).

2. We have given our publisher partners ultimate control via process and technology-driven quality measures. Publishers have the power to select recommendations that align with their brand—their editorial voice, their audiences needs, and what they do and don’t like—using simple levers. For example, link zappers, whitelists, blacklists, blocking by keyword, domain, campaign, and advertiser, image sensitivity, and improved visualizations of everything on page for publishers. This is supported by “always-on” network monitoring.

3. Outbrain has launched and improved its network-oversight to drive and uphold the highest standards in the industry around fraud, transparency & disclosure, brand safety, viewability, ad verification, privacy and policy. Through this team we operate “always-on” network monitoring to identify and remove unwanted or inappropriate content—both through human intervention and technology (internal e.g. continuous automated monitoring and external e.g. WebPurify).

When you support journalism on the open web and curate all the publishers that you accept into your network, the possible margin for error is severely reduced. Yet, as media outlets continue to fine-tune their algorithms and data analysis methodologies, it’s important for consumers to keep in mind that there is, indeed, a distinction between fake news and factual news that is labeled as fake.